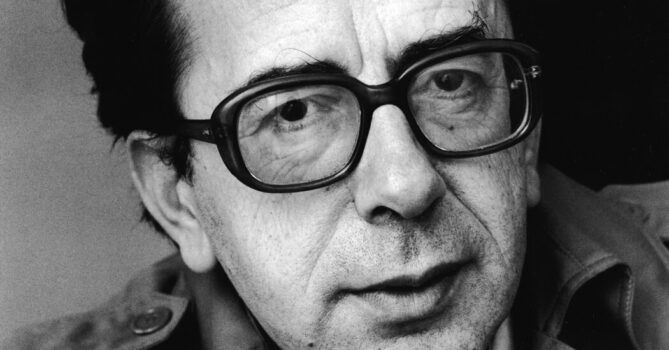

Ismail Kadare, the Albanian novelist and poet who single-handedly wrote his remoted Balkan homeland onto the map of world literature, creating typically darkish, allegorical works that obliquely criticized the nation’s totalitarian state, died on Monday in Tirana, the Albanian capital. He was 88.

His loss of life was confirmed by Bujar Hudhri, the pinnacle of Onufri Publishing Home, who was his editor and writer in Albania. He mentioned that Mr. Kadare went into cardiac arrest at his house and died at a hospital.

In a literary profession that spanned half a century, Mr. Kadare (pronounced kah-dah-RAY) wrote scores of books, together with novels and collections of poems, brief tales and essays. He shot to worldwide fame in 1970 when his first novel, “The Basic of the Lifeless Military,” was translated into French. European critics hailed it as a masterpiece.

Mr. Kadare’s identify was floated a number of instances for the Nobel Prize in Literature, however the honor eluded him. In 2005, he obtained the inaugural Man Booker Worldwide Prize (now the Worldwide Booker Prize), awarded to a dwelling author of any nationality for total achievement in fiction. The finalists included such literary titans as Gabriel García Márquez and Philip Roth.

In awarding the prize, the British critic John Carey, the panel’s chairman, known as Mr. Kadare “a common author in a practice of storytelling that goes again to Homer.”

Critics typically in contrast Mr. Kadare to Kafka, Kundera and Orwell, amongst others. In the course of the first three a long time of his profession, he lived and wrote in Albania, which on the time was underneath the grip of one of many Jap bloc’s most brutal and idiosyncratic dictators, Enver Hoxha.

To flee persecution in a rustic the place greater than 6,000 dissidents have been executed and a few 168,000 Albanians have been despatched to jail or labor camps, Mr. Kadare walked a political tightrope. He served for 12 years as a deputy in Albania’s Folks’s Meeting, and he was a member of the regime’s Writers Union. Considered one of Mr. Kadare’s novels, “The Nice Winter,” was a good portrayal of the dictator. Mr. Kadare later mentioned he had written it to curry favor.

In distinction, a number of of his most sensible works, together with “The Palace of Goals” (1981), subversively attacked the dictatorship, skirting censorship by way of allegory, satire, fantasy and legend.

Mr. Kadare “is a supreme fictional interpreter of the psychology and physiognomy of oppression,” Richard Eder wrote in The New York Times in 2002.

Ismail Kadare was born on Jan. 28, 1936, within the southern Albanian city of Gjirokaster. His father, Halit Kadare, was a civil servant; his mom, Hatixhe Dobi, who ran the house, was from a rich household.

When Hoxha’s communists seized management of Albania in 1944, Ismail was 8 years outdated and already immersing himself in world literature. “On the age of 11 I had learn ‘Macbeth,’ which had hit me like lightning, and the Greek classics, after which nothing had any energy over my spirit,” he recalled in a 1998 interview with The Paris Evaluate.

But, as an adolescent, he was drawn to communism. “There was an idealistic facet to it,” he mentioned. “You thought that maybe sure facets of communism have been good in idea, however you could possibly see that the observe was horrible.”

After finding out at Tirana College, Mr. Kadare was despatched for postgraduate examine to the Gorky Institute for World Literature in Moscow, which he later described as “a manufacturing facility for fabricating dogmatic hacks of the socialist-realism college.”

In 1963, about two years after his return from Moscow, “The Basic of the Lifeless Military” was printed in Albania. The novel is about an Italian basic who returns to the mountains of Albania 20 years after World Warfare II to disinter and repatriate the our bodies of his troopers. It’s a story of the superior West intruding into a wierd land, dominated by an historic code of blood feuds.

Professional-government critics condemned the novel for being too cosmopolitan and for not expressing enough hatred for the Italian basic, but it surely made Mr. Kadare a nationwide movie star. In 1965, the authorities banned his second novel, “The Monster,” instantly after its publication in {a magazine}.

In 1970, when “The Basic of the Lifeless Military” was printed in a French translation, it took “literary Paris by storm,” The Paris Evaluate wrote.

Mr. Kadare’s sudden prominence drew the surveillance of the dictator himself. To placate the regime, Mr. Kadare wrote “The Nice Winter” (1977), a novel celebrating Hoxha’s break with the Soviet Union in 1961. Mr. Kadare mentioned he had three decisions: “To evolve to my very own beliefs, which meant loss of life; full silence, which meant one other sort of loss of life; or to pay a tribute, a bribe.” He selected the third answer, he mentioned, by writing “The Nice Winter.”

In 1975, after he wrote “The Purple Pashas,” a poem criticizing members of the Politburo, Mr. Kadare was banished to a distant village and barred from publishing for a time.

His response got here in 1981, when he printed “The Palace of Goals,” a damning critique of the regime. Set throughout the Ottoman Empire, it portrays an unlimited forms dedicated to accumulating the goals of its residents, trying to find indicators of dissidence. In The Instances, Mr. Eder described it as a “moonlit parable concerning the madness of energy — murderous and suicidal on the identical time.” The novel was banned in Albania, however not earlier than it offered out.

Mr. Kadare’s success overseas afforded him some safety at house. Nonetheless, he mentioned, he lived with the worry that the regime may “kill me and say that it was a suicide.”

To guard his work from manipulation within the occasion of his loss of life, Mr. Kadare smuggled manuscripts out of Albania in 1986 and delivered them to his French writer, Claude Durand. The writer in flip used his personal journeys to Tirana to smuggle out further writings.

The cat-and-mouse sport through which the regime by turns printed and banned Mr. Kadare’s works continued previous Hoxha’s loss of life in 1985, till Mr. Kadare fled to Paris in 1990. After the regime’s collapse, Mr. Kadare got here underneath assault from anticommunist critics, each in Albania and within the West, who portrayed him as a beneficiary and even an lively supporter of the Stalinist state. In 1997, when his identify was being talked about for the Nobel, an article within the conservative Weekly Customary urged the committee to not award him the prize due to his “aware collaboration” with the Hoxha regime.

Apparently to inoculate himself in opposition to such criticism, Mr. Kadare printed a number of autobiographical books within the Nineties through which he urged that he had resisted the regime, each spiritually and artistically, by way of his literature.

“Each time I wrote a e-book,” he mentioned within the 1998 interview, “I had the impression that I used to be thrusting a dagger into the dictatorship.”

Writing in 1997 in The New York Evaluate of Books, Noel Malcolm, an Oxford historian, praised the “atmospheric density” and “poetic tautness” of Mr. Kadare’s writing, however chastised his defensiveness with critics.

“The creator doth protest an excessive amount of,” Mr. Malcolm wrote, warning that Mr. Kadare’s “elisions and omissions” of his “self-promoting volumes” may harm his fame greater than his critics’ assaults. Mr. Kadare’s most significant works “passed off on a distinct airplane, directly extra human and extra mythic, from that of any kind of ideological artwork,” he wrote.

In a thin-skinned response, Mr. Kadare accused Mr. Malcolm of exhibiting cultural vanity in opposition to an creator from a small nation.

“To take such a liberty with a author simply because he occurs to come back from a small nation is to disclose a colonialist mentality,” he wrote in a letter to The New York Evaluate of Books.

Mr. Kadare’s survivors embody his spouse, Elena Kadare, additionally an creator, and two daughters: Besiana Kadare, a former Albanian ambassador to the United Nations, and Gresa Kadare.

After the collapse of communism, Mr. Kadare continued to set his novels amid the suspicion and terror of the Hoxha regime. A number of, nonetheless, portrayed Albanians dwelling in Twenty first-century Europe however nonetheless haunted by their nation’s blood feuds, legends and myths. His best-known works embody “Chronicle in Stone” (1971); “The Three-Arched Bridge” (1978); “Agamemnon’s Daughter” (1985); its sequel, “The Successor” (2003); and “The Accident” (2010).

All his works shared a energy, Charles McGrath wrote in The Times in 2010: Mr. Kadare is “seemingly incapable of writing a e-book that fails to be fascinating.”

In 2005, after he received the Booker Worldwide Prize, Mr. Kadare mentioned, “The one act of resistance doable in a basic Stalinist regime was to write down.”

Amelia Nierenberg contributed reporting.